|

|

A fine hand coloured Edwardian postcard, of Loftus Mill Bank, (called Kilton Bank here).

Of interest is the gates leading to the park on the right, the road is much wider now at this point. In the distance on top of the cliff, the works are only a small part of what it later became. Skinningrove (Loftus) mine in the valley, still has the large chimney, with the steam raising boilers used to power the mine.

Postcard courtesy of Tina Dowey.

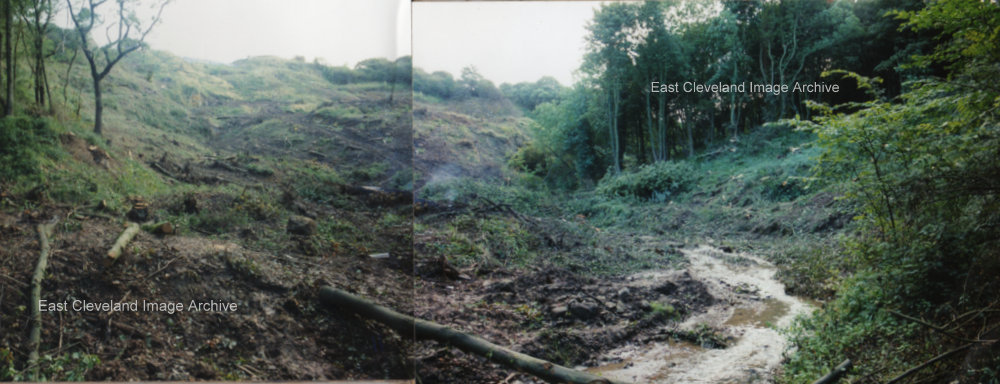

After specialist work by rock climbers on the steep cliff face of the narrows, work begins on removing 20,000 tons of unstable ground. And then replacing it with 200,000 tons of fill, using excavated materials from the Skelton and Brotton Bypass then under construction. This occupied the rest of 1999, at first weight restrictions and traffic lights were used to ease traffic flow. But when the bank closed, a 15 mile diversion was in force, via the A171 road over the North York moors.

Image and detail courtesy Keith Ferry.

Loftus Bank; this montage of photographs shows the construction of the culvert to channel Whitecliffe Beck past the Landslip. It was 173 metres long, with a tunnel for the sewer 140 metres long. At the top of the bank the existing road was removed and replaced, with a retaining wall 65 metres long and 4 metres high being constructed. It was one of the biggest engineering projects ever undertaken by Redcar and Cleveland Council. During the works, Road traffic was routed onto the North York Moors A171 road. A 15 mile detour to Teesside, at a cost of £3,000,000. The road finally opened to controversy on September 29th 2000, some nineteen months after the first slip.

Image and detail courtesy Keith Ferry.

The devastation after the massive landslide, on Mill Bank Loftus, February 1999.

Image courtesy Keith Ferris.

Whitecliffe beck and wood, Loftus; before the landslip, in 1999.

Image courtesy Keith Ferry.

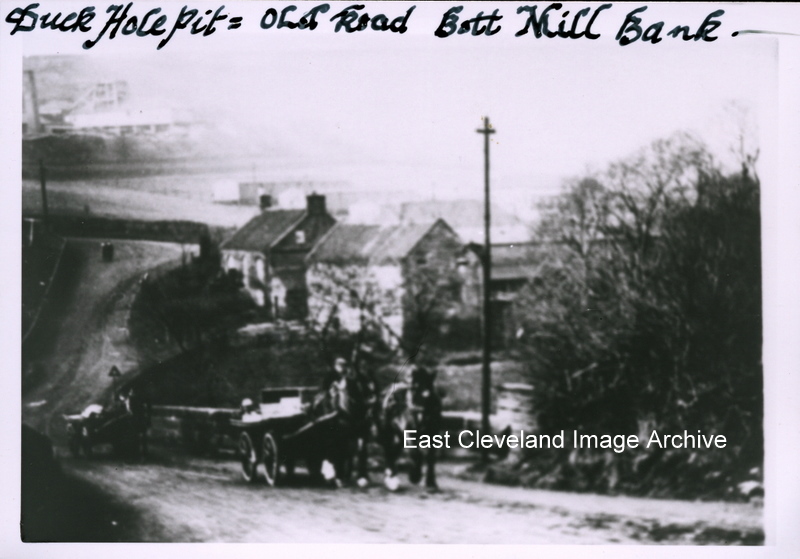

A cart – double horse drawn – starts the climb of Loftus ‘Mill’ bank, in the background is Carlin How (Duckhole) mine which started production in 1873. In the field below the mine you can see rows of prefabricated dwellings which were built in 1915 to house miners brought to replace those engaged in the war. It is now known they were used to accommodate Australian servicemen during the same period. The only buildings still recognisable are Kilton mill and house in the foreground. Susan Brown adds: “My maternal grandfather Joseph Holliday worked at the Duckhole mine. I think my gran’s second husband Frank Cuthbert may have worked there too.“

Image courtesy of Keith Bowers; many thanks to Howard Wilson for an update regarding the Australian connection, also thanks to Susan Brown for the update.

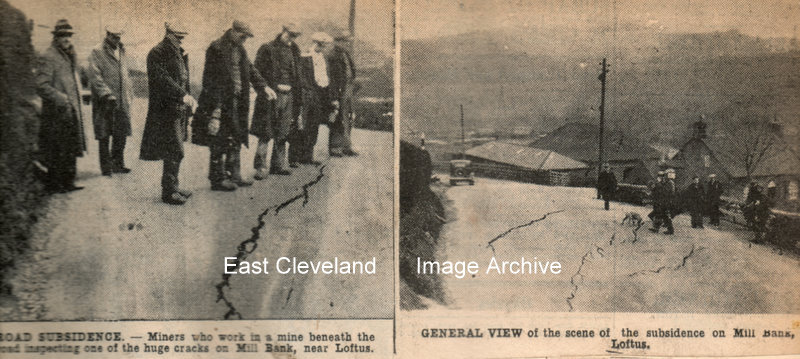

Miners who work in a mine beneath the road inspecting one of the huge cracks on Mill Bank, 2nd of March 1937.

Images are from our cuttings file (in the main from the Evening Gazette).

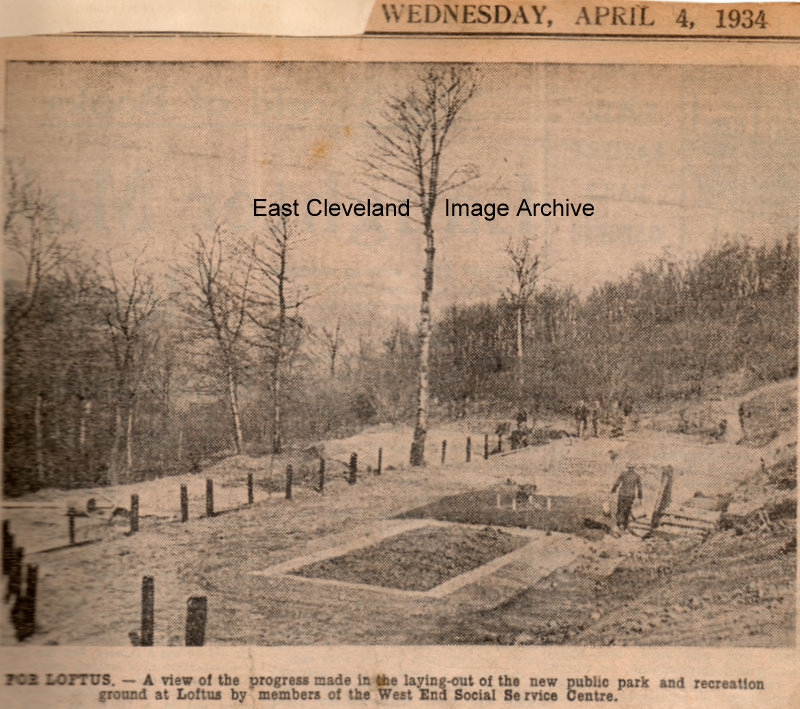

A piece of land on Mill Bank was let for a nominal fee by the Marquis of Zetland and the park was made by 80 volunteers from the Loftus West Road Social Centre, one of the schemes for relieving the monotony of the unemployed, transforming 3 acres of wooded land into a beauty spot, the park and children’s recreation ground is hoped to have swings, a sand pit and other attractions.

Images are from our cuttings file (in the main from the Evening Gazette), thanks to Maurice Dower for the update.

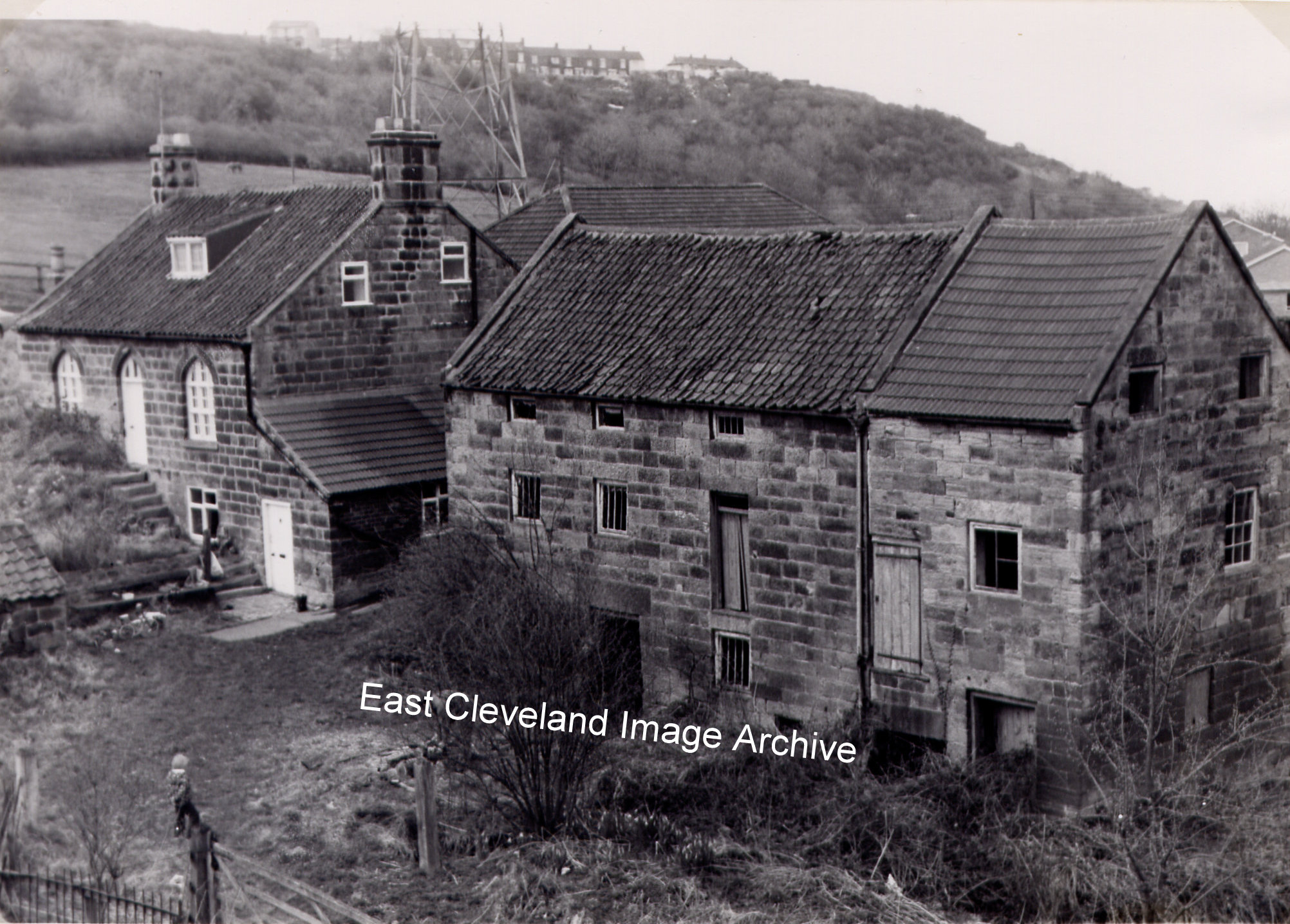

Kilton Mill, an image of the building taken from the ’new’ road embankment after 1973.

Image courtesy of the Pem Holliday Collection.

This is Kilton Mill, before the ”new” Mill Bank was created. Kilton Mill at the bottom of Mill Bank, used Kilton Beck water, which was diverted from Kilton Beck at the ‘Long Dump’, just downstream from the Culvert. It’s name came from the fact that this was the most accessible point from Kilton (and the castle) for a watermill to be built.

Thanks to Tony and Norman Patton for updates.

|

|

Recent Comments